Sweden’s green industry hopes hit by Northvolt woes

- আপডেট সময়: শুক্রবার, ৩ জানুয়ারি, ২০২৫

- ৪ টাইম ভিউ

[ad_1]

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHeavy snow blends into white thick clouds in Skellefteå, a riverside city in northern Sweden that is home to 78,000 residents.

It’s also the location of what was supposed to become Europe’s biggest and greenest electric battery factory, powered by the region’s abundance of renewable energy.

Swedish start-up Northvolt opened its flagship production plant here in 2022, after signing multi-billion euro contracts with carmakers including BMV, Volkswagen and Nordic truck manufacturer Scania.

But it ran into major financial troubles last year, reporting debts of $5.8bn (£4.6bn) in November, and filing for bankruptcy in the US, where it had been hoping to expand its operations.

Since September it’s laid off around a quarter of its global workforce including more than 1,000 staff in Skellefteå.

“A lot of people have moved out already,” says 43-year-old Ghanaian Justice Dey-Seshie, who relocated to Skellefteå for a job at Northvolt, after previously studying and working in southern Sweden.

“I need to secure a job in order to extend my work permit. Otherwise, I have to exit the country, sadly.”

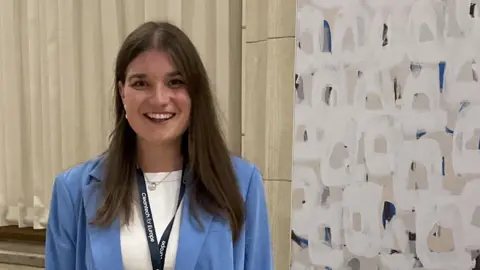

Maddy Savage

Maddy SavageMany researchers and journalists tracking Northvolt’s downfall share the view that it was at least partly caused by a global dip in demand for electric vehicles (EVs).

In September Volvo abandoned its target to only produce EVs by 2030, arguing that “customers and markets are moving at different speeds”. Meanwhile China, the market leader in electric batteries, has been able to undercut Northvolt’s prices.

Missing production targets (a key factor in BMW pulling out of a €2bn deal in June), expanding too quickly, and the company’s leadership have also been widely cited as factors fuelling the crisis.

“To build batteries is a very complex process. It takes a lot of capital, it takes time, and they obviously just didn’t have the right personnel running the company,” argues Andreas Cervenka, a business author and economics commentator for Swedish daily Aftonbladet.

At Umeå university, Madeleine Eriksson, a geographer researching the impact of so-called “green industries” says Northvolt presented a “save the world mentality” that impressed investors, media and local politicians.

But this “now-or-never” approach, she argues, glossed over the fact it was a risk-taking start-up that “never finished attracting investment”.

Northvolt did not respond to multiple requests from the BBC to respond to comments about its downfall or future plans.

The firm has hired German Marcus Dangelmaier, from global electronics company TE Connectivity to run Northvolt’s operations in Skellefeå, from January, as it seeks to attract fresh investment.

Northvolt’s co-founder and CEO Peter Carlsson – a former Tesla executive – resigned in November.

As the postmortem into the crisis continues, there are debates about the potential impact on Sweden’s green ambitions.

Northern Sweden, dubbed the “Nordic Silicon Valley of sustainability” by consultancy firm McKinsey, has swiftly gained global reputation for new industries designed to fast-track Europe’s green transition.

The region is a hub for biotech and renewable energy. Alongside Northvolt, high profile companies include Stegra (formerly called H2 Green Steel) and Hybrit, which are both developing fossil-free fuel using hydrogen.

But Mr Cervenka, the economics commentator, argues Northvolt’s downfall has damaged Sweden’s “very good brand” when it comes to green technologies.

“There was a huge opportunity to build this champion, and to build this Swedish icon, but I think investors that lost money are going to be hesitant to invest again in a similar project in the north of Sweden,” he says.

Some local businesses say the publicity around Northvolt’s crisis is already having a negative impact.

“I feel it myself when I travel now – even to the southern parts of Sweden – and abroad, that people really ask me questions,” says Joakim Nordin, CEO of Skellefteå Kraft, a major hydropower and wind energy provider, which was an early investor in Northvolt.

Cleantech Scandanavia

Cleantech ScandanaviaHeadquartered in Malmö in southern Sweden, Cleantech for Nordics is an organisation that represents a coalition of 15 major investors in sustainability-focussed start-ups.

Here, climate policy analyst Eva Andersson believes the nation’s long legacy as an environmental champion will remain relevant.

“I think it would be presumptuous to say that, okay, now we are doomed here in the Nordics because one company has failed,” she argues.

Cleantech for Nordics’ research suggests there were more than 200 investments in clean tech projects in Sweden in 2023.

Another study by Dealroom, which gathers data on start-ups indicates 74% of all venture capital funding to Swedish start-ups went to so-called impact companies which prioritise environmental or social sustainability, compared to a European average of just 35%.

“Sweden is still punching above its weight in this sector. And I think we could expect it to continue to do so moving forward as well,” predicts Anderson.

There are growing calls for increased state support to help Sweden maintain its position. The Swedish government refused to bail out Northvolt, suggesting all startups – sustainable or not – should be subject to market forces rather than bailed out by taxpayers. But as other parts of the world ramp up battery production and other carbon-cutting industries, the decision has faced a backlash.

“The US and China have massive support packages for green industry, and they definitely are catching up and overtaking in some sectors. And so that is definitely a threat to be reckoned with,” argues Andersson.

Just 3% of global battery cell production currently takes place in Europe – according to research for international consultancy firm McKinsey – with Asian firms leading the market.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSweden’s minister for Energy, Business and Industry Ebba Busch argues more EU support rather than funding from individual governments is the answer.

Last month she told Swedish television the situation at Northvolt was “not a Swedish crisis”, rather a reflection of a Europe-wide challenge when it comes to competitiveness in the electric battery sector.

But while the government insists it wants Sweden to play a key role in Europe’s battery industry, and the wider green transition, it has been accused of sending mixed messages. The right-wing coalition, which came into power in 2022 has cut taxes on petrol and diesel, and abolished subsidies for EVs.

“This is a very politically sensitive area,” says journalist Cervenka. “The Swedish government is being actually criticised internationally for not fulfilling its climate obligations. And that is a stark contrast to the image of Sweden as a pioneer.”

The BBC approached Busch’s media team, but was not granted an interview.

Skellefteå Kraft

Skellefteå KraftBack in Skellefteå, where it has been dark since just after lunch, Joachim Nordin is preparing to commute home in the snow.

He says there’s a strong industrial will for Sweden to remain a green tech role model, despite policymakers being “not as ambitious” as previous administrations.

The criteria that enticed Northvolt to establish its first factory in Skellefteå will also attract other big global players to the region, according to the energy company CEO.

“It’s 100% almost renewable energy up here… and that’s that’s pretty unique if you compare it to the rest of Europe. But on top of that we are among the cheapest places in the world for the electricity prices. So if you combine those two things, it’s a huge opportunity.”

Skellefeå Kraft recently announced a collaboration with Dutch fuel company Sky NRG. Their ambition is to open a large factory by 2030, making fossil-free plane fuel (produced using hydrogen combined with carbon dioxide captured from biogenic sources).

“The publicity around Northvolt is not helping now, of course. But I hope that that’s just something that will be remembered as a little bump in the road, when we look back at this 10 years from now,” says Mr Nordin.

[ad_2]

Source link

Man charged with assaulting partner before her death in hospital allegedly used ‘axe handle’: court